The discovery of intricate engravings depicting fish and fishing nets at the Ice Age campsite of Gönnersdorf, located along the Rhine River, has offered unprecedented insights into early fishing practices and the symbolic world of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers. This research, conducted by a team from Monrepos, a division of the Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie in Germany, in collaboration with Durham University, was published in PLOS ONE and represents a significant step forward in our understanding of the social, symbolic, and subsistence activities of the Late Upper Paleolithic period, around 20,000–14,500 years ago.

The Gönnersdorf site is one of Europe’s richest sources of Ice Age art, housing hundreds of engraved schist plaquettes. These stone artifacts showcase detailed depictions of prey animals such as wild horses, woolly rhinos, reindeer, and mammoths, all critical to the survival of the human groups who occupied the camp approximately 15,800 years ago. In addition to these animals, the site is renowned for its stylized engravings of female figures, providing valuable insights into the symbolic practices of these early communities. Now, with new advanced imaging methods, Gönnersdorf has also yielded the earliest known depictions of fishing techniques, specifically using nets or traps—an invaluable contribution to our understanding of prehistoric subsistence strategies.

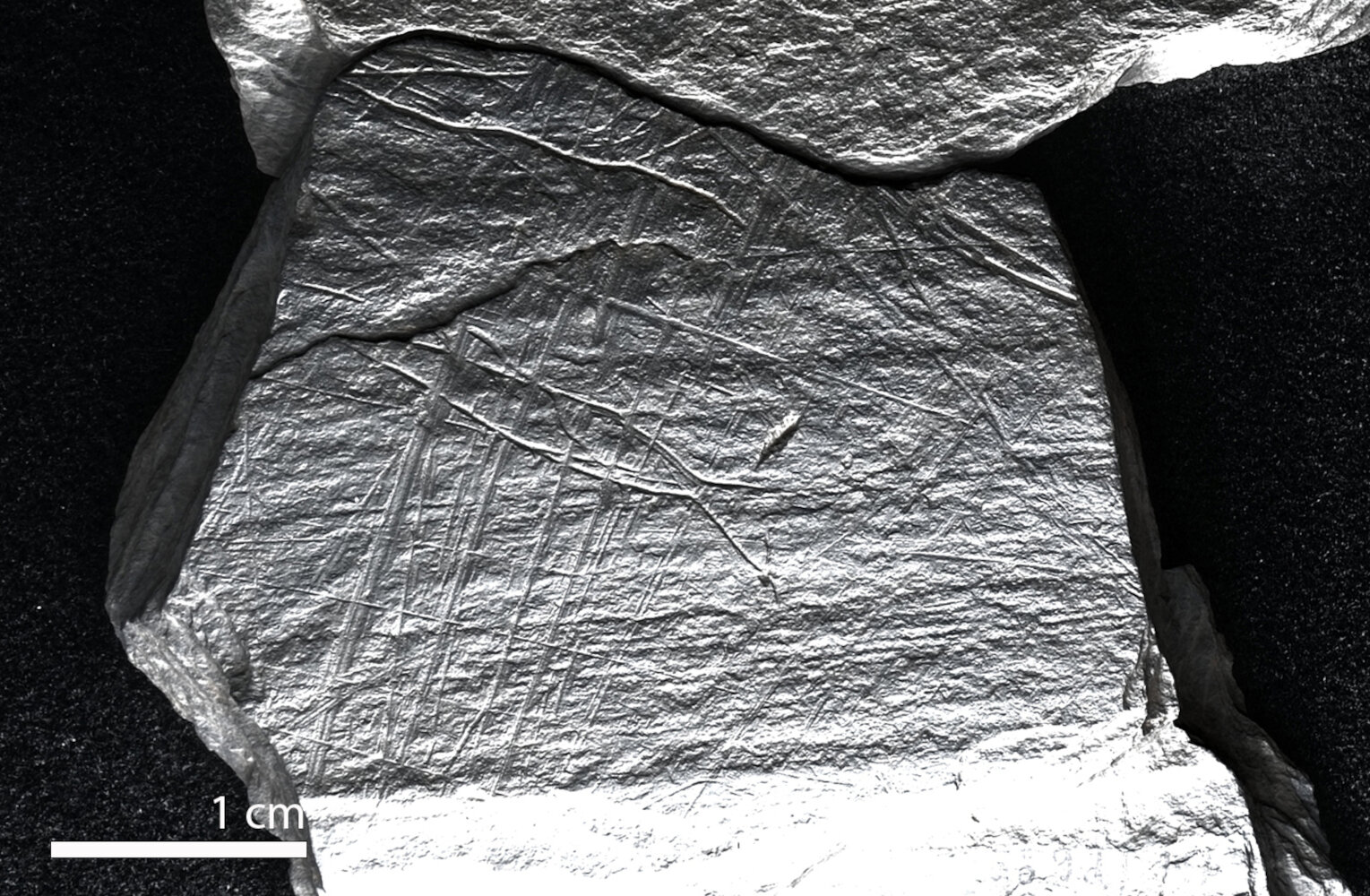

The interdisciplinary team, composed of experts from Durham University’s Archaeology and Psychology departments and the MONREPOS Archaeological Research Center and Museum for Human Behavioral Evolution, applied cutting-edge imaging techniques to examine these engravings. Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), a method allowing detailed analysis of surface engravings, was particularly useful in identifying intricate carvings on the plaquettes that had previously gone unnoticed. The technology revealed delicate engravings of fish, covered with grid-like patterns that researchers interpret as representations of fishing nets or traps. This discovery is the earliest known visual evidence of net or trap fishing in European prehistory and challenges previous assumptions about the complexity and antiquity of fishing technology among Paleolithic societies.

Fishing has long been recognized as an essential part of the Paleolithic diet, but until now, archaeologists had no direct evidence of the specific methods these early people used to catch fish. The engraved depictions of nets or traps at Gönnersdorf serve as a rare visual record of an ancient technology that typically would not survive in the archaeological record due to the perishable materials likely used. This finding suggests that fishing technologies might have been well-developed much earlier than previously assumed, indicating a high level of technical skill among these communities.

Beyond the technological aspect, the engravings suggest that fishing held symbolic or social significance. Until now, Ice Age art primarily focused on animals, but the depictions at Gönnersdorf reveal that activities, not just fauna, were important themes for these people. The presence of fish and fishing nets among traditional prey animals may indicate that fishing was not only a means of survival but also held a deeper meaning in their cultural or spiritual lives.

The study also explored the artistic processes behind these engravings, delving into how early humans might have created and interpreted them. The team examined individual cut-marks on the plaquettes, which allowed them to identify specific artistic “styles” and potentially even individual artists. They also observed that the shapes of the plaquettes themselves, along with natural cracks and ridges, influenced where and what would be engraved. This phenomenon, known as pareidolia, is when the brain interprets random patterns as meaningful shapes, such as seeing faces in clouds. The natural forms of the plaquettes may have inspired artists to create images that interacted with the stone’s features, blending nature and art in unique ways.

This discovery enriches our understanding of the role of art and symbolism in Ice Age societies, suggesting that the creation and interpretation of these images were not merely decorative but integral to the social and symbolic fabric of the time. By combining archaeological analysis with visual psychology, the researchers hope to gain a more comprehensive view of how ancient humans viewed and engaged with the world around them.

The findings at Gönnersdorf underscore the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in archaeology, particularly when investigating the lives of early humans. As technology advances, researchers can reveal increasingly nuanced aspects of ancient life that were previously inaccessible. The discovery of fishing depictions at Gönnersdorf not only expands the known repertoire of Ice Age art but also encourages a re-evaluation of how ancient people interacted with their environment and integrated practical knowledge into their symbolic and artistic expressions. This research reminds us that human societies, even tens of thousands of years ago, were complex, adaptive, and deeply connected to both their subsistence practices and cultural identities.